History Knox

Mark Jordan's History Knox column is published each Saturday at Knox Pages

FREDERICKTOWN — The news this week of a bank robbery in Centerburg reminded me of Knox County’s infamous 1934 bank robbery in Gambier by members of John Dillinger’s gang, which we’ve talked about here before.

A lesser-known event, though, is the robbery that took place on Dec. 30, 1933, in Fredericktown.

Digging into the story proves that it is no less fascinating, not least of all since it might be the work of a now-forgotten female criminal mastermind.

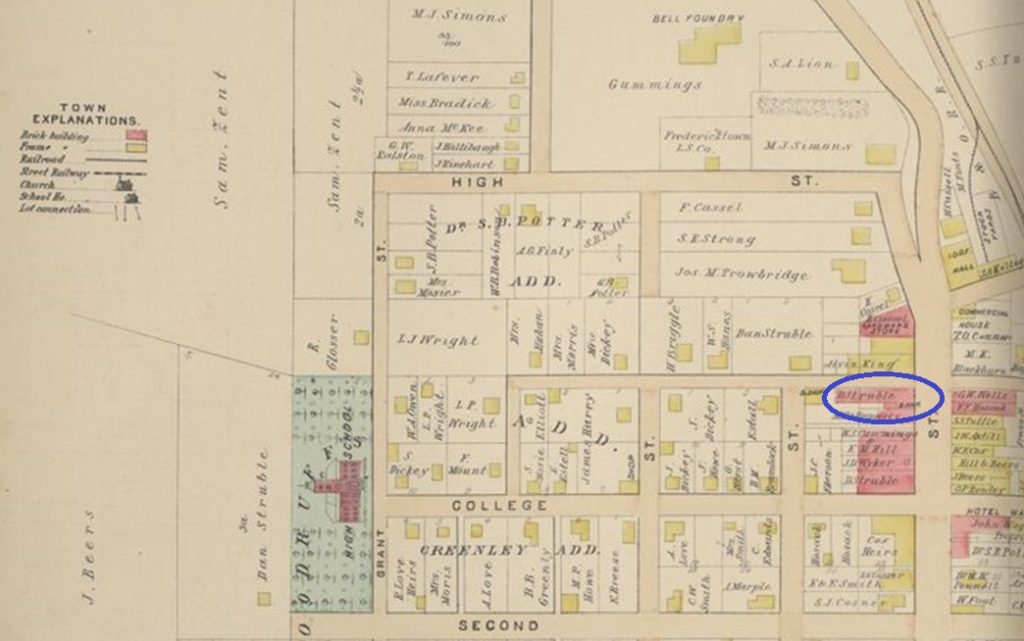

The target was a typical small-town financial institution. The Dan Struble & Son Bank was incorporated in Fredericktown in 1930, with a surety of $25,000 registered with the Ohio secretary of state.

The investors listed on that document were Helen Struble, D.L. Wells, and Charles and Bertha Ackerman. The paperwork was filed by their lawyer, W.J. Sperry of Mount Vernon.

This appears to have been a reorganization of the original Stuble & Son Bank, which had been in business since the 1870s.

The original president, Dan Struble, had passed away years ago. His son Ralph took it over and operated it until his death in 1930. Helen, his wife and inheritor of the bank, reorganized it after her husband’s death. Charles Ackerman was the head cashier, and others were hired to assist him.

On the Saturday in question in late 1933, Ackerman was working, as well as cashier F.L. Barnes, and tellers Dorothy Scarbrough and Veronica Harlett. Just a few minutes before noon, farmers Charles Ewers and John Adams were in the lobby of the bank, making transactions.

A black Plymouth sedan pulled up in front of the bank, which was located on the corner of North Main and West First Streets (where the Park National Bank is today). The driver remained in the car while two men got out. One was dressed in overalls with a jacket. The other was dressed in a dark suit with a long coat.

Instead of walking into the front door, the two men walked to the side entrance. Entering briskly, they whipped out guns and wasted no time in making their purpose known. Both men held a revolver in each hand, and the getaway driver could be seen through the window to be armed as well.

“This is a hold-up,” one of the men announced. “Down on the floor, all of you. We mean business.”

The man in the overalls quickly judged that Ackerman was in charge and pointed his gun at the banker while the man in the suit herded the clerks and customers to the wall and made them lie down on the floor on their backs.

“Open up that vault,” the man in overalls said to the bank president. “Open it or I’ll kill you.”

After a helpless moment, Ackerman said, “You’ll have to shoot, because the time lock has been set and the vault can’t be opened.”

The robber was furious and thought Ackerman might be lying, but he was in fact telling the truth. It was Saturday, and the bank was about to close at noon. Ackerman had already triggered the vault to close, and it was connected to a timer that would not permit it to open until Monday morning. Ackerman demonstrated the equipment to the gunman.

If Ackerman knew of any way to override the security system, he kept it to himself.

The robbers decided not to spend any further time on the vault and quickly set to emptying the tills. They gathered what was later estimated at around $6,000 in cash, an amount that would today be valued over $140,000.

They grabbed Ackerman and led him at gunpoint out to the car and forced him to get in the back. The vehicle took off, headed up the hill toward the square, where it turned right on the Mount Gilead Road (today known as Ohio State Route 95).

Ackerman was terrified, but tried not to panic, saying nothing. At the edge of town, the driver suddenly stopped the car, and the gunman in the back seat pushed Ackerman out of the vehicle.

He survived his kidnapping experience without harm.

Cashier F.L. Barnes had quickly jumped into action after his boss was kidnapped. As soon as the robbers were out the door, Barnes was on the phone to the police. He then ran out onto the sidewalk and was able to read the license plate numbers of the Plymouth as it sped up North Main.

He gave the number to the police, who arrived quickly. While state highway patrol cars in the region were alerted to be on the lookout, the plate number was traced to a registration from New London, in Huron County.

The Plymouth was found later that day in northern Richland County, abandoned on a country road. It had been stolen.

Less than a month later, authorities found a man and his girlfriend in possession of money in wrappers from the Dan Struble & Son Bank. They had purchased a new car in Chicago, with cash.

Sam Harper — also known by the alias Robert Weston — was arrested along with his girlfriend Gladys Crawford, who was found to have possession of more money with wrappers identifying it as from the Fredericktown bank. Under questioning, the pair confessed.

Sam Harper, 31, was also identified as the gunman in a robbery of a bank in Cullen, Illinois, therefore the Chicago police determined to keep him in Illinois to be put on trial for that crime.

Remarkably, although the police described Gladys Crawford as “the brains” of the gang, she was released after Harper agreed to take the entire blame. Harper named the two men who assisted him in the Fredericktown robbery as Roscoe Cutler and Albert Slade.

Cutler, the driver, was found and arrested just days later. Both men were ex-cons, Harper having escaped from prison just before his spree of three bank robberies.

If the authorities released Gladys Crawford, further research suggests they made a huge mistake.

This woman, born Gladys LaRue, had as early as 1930 been investigated for suspicion of involvement in 10 bank robberies, some of which she may have participated in dressed in men’s clothes.

In and out of jail for many years, Crawford seems to have indeed been the driving force in a long string of bank robberies in the Midwest in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Her criminal experience surfaced by 1927, when she was still in her late teens and was charged with involvement in a counterfeiting ring.

By 1930, she was involved with the notorious Corray Gang of bank robbers, suspected in 11 robberies. The Corray brothers tried to spare Gladys by pleading guilty when they were put on trial, denying the young woman had any part in the whole robbery plot.

As soon as she was dismissed, however, she was re-arrested for other robberies.

After the Corrays were taken off the streets and Gladys served a brief sentence, she was back in the thick of it with Sam Harper.

One wonders if Albert Slade existed at all, or if it was a fake name for Gladys herself disguised as a man for the Fredericktown robbery. More likely is that “Albert” was an alias for George Slade, a known robber at times associated with Pretty Boy Floyd, and who was later regarded as Crawford’s common-law husband.

When Harper and Crawford were arrested in Chicago, the dangerous duo and a safe-blowing accomplice were caught with an arsenal of over 40 guns, including machine guns, silencers, and over three feet of bomb fuse and the gunpowder to use with it.

Remarkably, the men once again took the fall for Gladys, who was released, uncharged, despite her long history of involvement with bank robbery gangs.

She surfaces once more in the late 1930s on narcotics charges in Peoria, Illinois, before sinking back into the murk of history. It’s unlikely we’ll ever know if she was truly the brains behind the Fredericktown robbery, but it seems not just possible, but probable.

In her criminal career, Gladys Crawford, alias Gladys LaRue, alias Ruth Byron, and more, was suspected of counterfeiting currency, altering bonds, possessing illegal weapons, using drugs, selling drugs, planning or being otherwise involved in at least 20 bank robberies, and the subsequent laundering of stolen money from said robberies.

On top of all that, she had a remarkable ability to manipulate her male lovers into taking the fall for the crimes, while she went off to find another lover/accomplice. It’s hard to believe that today she is a completely forgotten figure of the Prohibition/Great Depression criminal era.

The Fredericktown bank itself continued on for many years.

Bank president Helen Struble Workman died in 1947. The bank board voted to consolidate the Dan Struble & Son Bank with the First-Knox National Bank in 1954. The original building was demolished later and replaced with the current structure, now Park National Bank.